I offer this 2013 sermon every year during Holy Week as my annual reminder that the Gospels we read during Holy Week reflect a vicious anti-Judaism that has contributed to misunderstanding and even hate by many Christians over the centuries. Let’s commit to hold these thoughts in context, regret and repent our historic institutional anti-Judaism as we gather for Holy Week services.

A Kaddish for Jesus

Maundy Thursday, March 28, 2013

A Kaddish for Jesus

Robin Garr

Sermon at St. Thomas Episcopal Church

Louisville, Kentucky

יִתְגַּדַּל וְיִתְקַדַּשׁ שְׁמֵהּ רַבָּא

Yitgaddal v’yitqaddash sh’meh rabba …

“Glorified and sanctified be God’s great name … ”

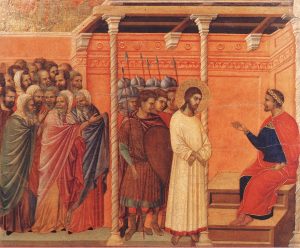

Christ Before Pilate Again (1308-1311), tempera painting on wood by Duccio di Buoninsegna (1255-1319). Museo dell’Opera Metropolitana del Duomo, Siena, Italy.

So begins Kaddish, the traditional Jewish prayer in which family members or friends honor the memory of a loved one who has died.

We gather this evening in memory of Jesus’s last supper with his friends, when he showed them the dignity of service and the meaning of humility by lovingly washing their feet.

Tomorrow, Good Friday, we’ll remember Jesus’s passion and death on the cross. Tonight, Jesus and his friends are sharing a Passover dinner. Within 24 hours, Jesus’s friends would have been sitting together, mourning his death with an ancient version of something like the Kaddish.

After all, Jesus and all his apostles were Jewish. They studied the Torah and they worshiped at the Temple in Jerusalem. Jesus was a rabbi, a teacher; many saw him as a prophet.

As we enter the three holy days of Jesus’s passion and death leading to the Easter joy of Christ’s resurrection, I’d like us to take a few minutes to remember – and honor – the Jewish tradition that Jesus believed and that Rabbi Jesus taught.

Now, you might be thinking, “Why bring this up?” Certainly it’s no secret that Jesus was Jewish and that Christianity is rooted in Judaism, sharing the same First Testament. But why go into all that now, during the holiest days on the Christian calendar?

I would suggest that there is no better time for us to think about our relationship with our Jewish brothers and sisters than now, when our scripture readings through Lent, Palm Sunday and Good Friday confront us with the harsh words that the leaders of the early church had for the Temple authorities.

Early in the Gospel of Luke, “the Jews” in Jesus’s home town got so angry with his first preaching that they chased him out of the synagogue and tried to throw him off a cliff. Luke goes on to tell how the Jewish scribes and priests were constantly spying on Jesus and trying to trick him into saying things that would get him in trouble.

In tomorrow’s Good Friday services we’ll hear John portraying “The Jews” as a nasty gang, out to get Jesus. They’re dead-set on making sure that the Roman governor Pontius Pilate won’t let Jesus off on a technicality. Earlier in the Gospel, John calls the Jews “children of the devil,” and warns that the Jewish authorities were constantly hatching plans to kill Jesus.

We hear “The Jews … The Jews … The Jews” like the beat of an angry drum. But as we listen to John’s Gospel tomorrow, let’s bear in mind that in Jesus’s time there were many Judaisms, not just one. Much like the church today, there was a huge variety of Jewish practices and scriptural interpretations, and they didn’t all get along.

Jesus very likely squabbled with a group of Temple authorities who saw nothing but a troublesome uproar over his active public ministry, his healings and his call for “good news for the poor.” In these days, especially at Passover time in Jerusalem, the Roman rulers weren’t shy about cracking down on anything that looked like trouble. This noisy rabbi was getting a lot of attention, and nobody wanted that!

And when Matthew wrote that “the Jews” shouted out to Pilate, “His blood be on us and our children,” he set down a vicious charge that would be hurled back at Judaism for 2,000 years. Placing the blame for Jesus’s death on “the Jews” set a flame that would ignite a shameful history of pogroms and persecutions and, eventually, the Holocaust.

In this post-Holocaust world, all people of good spirit look back and say, “never again.” To this end, let’s not just shrug off the anti-Jewish verses that still reside in our scriptural tradition.

It’s important to recognize that the stories about Jesus – the Gospels – were not written down until some 40 to 70 years after the crucifixion. Not many first-hand witnesses were still alive, and bad attitudes and prejudices had already built walls between Christians and Jews.

Forty years after the crucifixion, the Romans had destroyed the Temple, and most of Jerusalem with it. The Christian faith had reached out to embrace Gentile converts and was spreading across the Mediterranean and beyond, but its leaders still thought of the church as “Christian Jews.”

Judaism, meanwhile, focusing on the synagogue as center of community in a world without a Temple, now viewed the Christians as more than heretics. Christian Jews were thrown out of the synagogues and told to stay out. Everyone involved was human and flawed. Anger and tempers flared. It was in this fiery setting that the Gospel stories were written and the idea of “the Jews” as unrepentant killers of Jesus set in stone.

But as Marcus Borg points out in his recent book, Evolution of the Word, the Gospels don’t indict all Jews, only the individuals responsible for Jesus’s rejection – and, years later, the Christian community’s rejection from the synagogues. “To fail to recognize the historical circumstances and the limited intention of these passages,” Borg says, “is to perpetuate the long history of Christian anti-Semitism.”1

“His blood be on us and on our children”? “The scribes and chief priests … watched him and sent spies”? “The Jews, The Jews, The Jews”? When we hear these words during Holy Week, the holiest week of the year, let’s remember that it would not be inappropriate for us to pray Kaddish for Jesus:

“Yitgaddal v’yitqaddash sh’meh rabba … Glorified and sanctified be God’s great name throughout the world, which God has created according to God’s will. May God establish God’s kingdom in your lifetime and during your days, and within the life of the entire House of Israel, speedily and soon; and say, Amen.”

Think carefully about those words. Hear what they say. And now think about this: That first verse of Kaddish sounds a lot like the words that Jesus taught us when we asked him how to pray:

“Our Father in heaven, hallowed be your name. Your kingdom come. Your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven.”

Speedily and soon; and say, Amen.

––––––––––––––––

1Borg, Marcus J. (2012-08-28). Evolution of the Word: The New Testament in the Order the Books Were Written]. HarperOne. Kindle Edition.